AI In Practice

How SCA is developing ethical processes for using AI tools

by Desa Philadelphia

When people hear that more than 90% of the images in the 2025 student academy award-winning film The Song of Drifters were AI generated, the first question is usually: “So, what did the filmmaker actually do?’” A lot, it turns out. Despite what the headlines may have you believe, using AI, in practice, doesn't mean having AI do the work for you. At least not if you’re trying to create something compelling. So what, then, is AI good for? That’s the question SCA’s divisions are asking, and answering, as they develop workflows aimed at harnessing the technology’s storytelling potential.

“The School’s exploration of AI is taking place across every part of the school, including the classroom, the research lab, industry collaborations, and thought leadership,” says Holly Willis, Chair of the Media Arts + Practice division and Co-Director of AI for Media & Storytelling (AIMS), a practice-based studio under the auspices of USC's new Center for Generative AI and Society. “We're integrating it broadly, questioning it ethically, exploring its unknown threats and potentials, and showcasing our most innovative storytelling and new media experiences.”

The ethical aspect remains central to much of the work being done at the school. In an age when writers and artists are understandably upset that their work is being used to train AI tools without acknowledgement (or compensation!), SCA's approach is rooted not only in asking “What can we do?” but also in “What should we do?” It reflects the tried-and-true SCA method of engaging new technologies—teaching students to master current applications and investing in research to shape future uses.

For The Song of Drifters, filmmaker Xindi Zhang used her own watercolor artwork to train a bespoke model to create new imagery in her personal style. Using tools such as ComfyUI (powered by NVIDIA Cuda), Midjourney, TripoAI, Procreate Dreams, Blender, and After Effects, along with live-action footage shot on an iPhone 15 Pro, her animated film uses generative imagery as a storytelling instrument, not as a shortcut or visual effect. This imaginative application won her the 2025 Student Academy Award for Experimental Filmmaking. As the Expanded Animation Research + Practice (XA) division, from which Zhang graduated last year, noted: “The Song of Drifters is not just an award-winning student film, it is a glimpse into the future of animation as an expressive, adaptive, and deeply human art form in the age of AI.”

Behind the Scenes still from The Song of Drifters by Xindi Zhang.

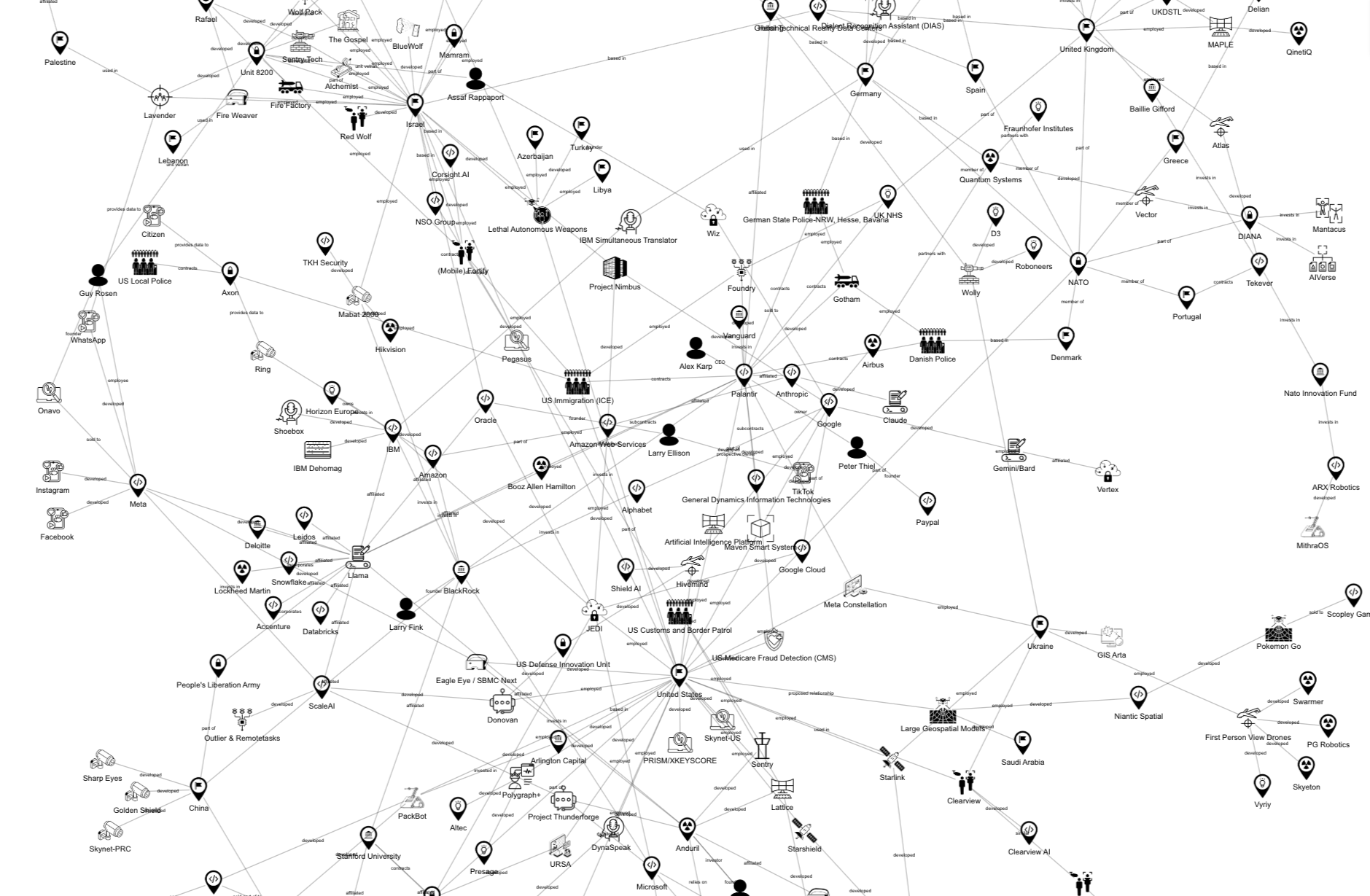

Zhang is among a growing number of SCA students and recent alumni expanding the conversations around AI and creativity. As part of her Ph.D. work in Media Arts + Practice, Sarah Ciston examined how the AI tools used for creativity are also being used for decision making by the military. Her project AI War Cloud: AI Decision-making from Battlefield to Desktop won the 2025 S+T+ARTS Grand Prize for Artistic Exploration, awarded by the European Commission to support projects merging technology and art. In the Expanded Animation Research + Practice Program, students are using animation, gesture and motion capture performance to train AI algorithms to artistically enhance, tell stories and humanize robots. In the Fall 2025 semester, several student projects across SCA divisions were developed through exploratory partnerships with leading technology companies, including Amazon Studios’ Future Cinema Creators Project and Google Flow Filmmaking Project.

In the classroom, students have room to experiment in ways that complement their learning. The class “Digital Media and Entertainment” in the Peter Stark Producing Program, now includes ways AI is used to create cinematic media, so that the program’s aspiring producers “can recognize what is required for high quality results.” In divisions like Interactive Media & Games, Media Arts + Practice and the John C. Hench Division of Animation + Digital Arts, discussions about integrating AI into workflows are now essential. A lot of the AI work involves determining which tools are useful, and which aren’t worth the time. “We’re doing listening sessions among faculty to stay abreast of the different tools that are coming online and, in some cases, quickly fading from use, then integrating AI, where appropriate, in specific courses” says Professor Jim Huntley, who leads USC Games’ Advanced Games Project. “It’s definitely something we’re integrating as a tool versus a replacement for human contribution.”

The realization that AI is ultimately no match for human creativity—(maybe even that describing something as “creative” requires that it has to be centered on human experience?)—has opened the door to embrace AI tools in ways that didn’t feel possible even a year ago. “We’re covering all the bases!” reiterates Holly Willis. “Whether we endorse or do not endorse the tools that have become available, it is our responsibility to train the next generation of storytellers, game designers, scholars, and media artists about the history, ethics, critical implications, environmental impacts, and functioning of a new paradigm of image-making and storytelling.” At the AI for Media & Storytelling Lab (AIMS)—a collaboration between SCA and the Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism—Willis works with students and faculty to “experiment with, invent, study, teach, and debate the power of AI for media and storytelling.”

Sarah Ciston’s PhD thesis project aiwar.cloud is an interactive installation showing how tools for creativity are also being used by the military.

The School’s research in AI is anchored by the Entertainment Technology Center (ETC), the think tank founded to support collaboration between industry and academia. There too, the emphasis is on assessing not only which tools work but how they should be used ethically. The Center’s AI & Neuroscience in Media Project (NIM) aims to help the media industry understand artificial intelligence and stay up to date on its developments. Its initiatives include thought leadership via a daily newsletter, an annual conference (The Synthetic Media Summit, which returns in early 2026), and monthly “AI Roundtables”, where creatives and leaders present their cutting-edge work. NIM is also driving industry-wide conversations towards the adoption of a written set of guidelines for the ethical practice of AI in media.

The NIM Project leads the AI Working Group, where ETC members share knowledge and develop industry guidelines on topics such as AI implementation, ethics, and metadata. It is currently spearheading the first phase of the Content Fingerprinting Initiative, which NIM director Yves Bergquist describes as “an attempt to create an industry-owned capability to identify and adjudicate, as precisely as possible, copyright violations in the output of generative AI models.” To accomplish this, Bergquist and his team are partnering with technology companies, studios, and academic researchers to build “technical sandboxes” that allow the industry to test and refine processes. “In the past, we successfully developed AI models to ensure moral and ethical guardrails for chatbots, and a semantic AI-driven language for narrative metadata in video,” Bergquist notes.

Not every program at SCA is accelerating AI usage. In Cinema & Media Studies, individual professors decide if AI can be used to aid research and writing, with many of those who allow it requiring disclosure. The John Wells Division of Writing for Screen & Television outright bans its use in script development, analysis, and writing classes. “If AI writes transitions or dialogue for you, you interrupt your growth as a writer, effectively relinquishing your creative voice and rights to a database. You lose your agency as a writer,” explains Wells Writing division Chair Mary Sweeney. “Our job in the Wells Writing Division is to help you identify, develop and preserve your unique creative voice. We want you to develop that voice by knowing yourself through original writing, to trust and cherish your own creative consciousness.” This is especially crucial as the Writers Guild of America presses studios to take legal action against tech companies that use writers’ scripts to train AI, as surfaced last year when it was revealed that more than 139,000 scripts from creators like SCA alumna Shonda Rhimes and other prolific showrunners, including Ryan Murphy and Matt Groening, were used to create an AI-training database.

With virtually non-existent legal precedent, it is important that SCA students learn to rely on their own creativity, even as they learn to use AI to work more efficiently. To that end, the ETC, which regularly funds experimental filmmaking, is supporting filmmakers already trained in traditional processes as they experiment with creating fully generative and hybrid short films. For writer/director Tiffany Lin, her film The Bends, set at the bottom of the ocean–an environment still largely unexplored–was designed to justify the use of generative AI as a medium. “Coming from the live-action and animation worlds, I wanted to ensure this was a story that truly warranted the medium,” Lin explains. “That took me to the bottom of the ocean—to something genuinely inaccessible.” (For more about the making of The Bends and Pathways, an ETC hybrid film, see the story about their creation in this issue).

Ultimately, the goal is the same as ever: to create impactful, engaging stories. AI is only as good as its usefulness in fulfilling the central tenet of creativity at the School of Cinematic Arts. Now that the fear around AI is dissipating, we can return to addressing the enduring and ever-baffling question that forever haunts our industry: What’s Next?

EXPLORING GENERATIVE AI FOR FILMMAKING

A behind the AI look at how the ETC films The Bends and Pathways were created

by Erik Weaver

The Bends is a fully generative short film directed by Tiffany Lin that merges the precision of traditional filmmaking with the innovation of AI-based production. Designed as both an artistic work and a technological benchmark, the project integrates virtual machines (VMs), GenJams, and a custom ShotGrid pipeline to orchestrate a cohesive and traceable creative process. Traditional department heads—production design, cinematography, animation, editorial, and sound—worked alongside AI researchers to maintain professional discipline standards while exploring the boundaries of generative media. ShotGrid supported production tracking, versioning, and metadata lineage, enabling a structured, studio-grade workflow across experimental AI systems.

The film leverages LoRA training, bespoke datasets, and procedural generation to develop characters whose transformation echo the story’s central theme: adaptation under pressure. Every phase—from model training through rendering—was subjected to rigorous creative supervision and version control, ensuring artistic integrity across outputs. Rendered in true 4K in 32-bit EXR format, the film underwent a unique stress test, as it was transferred to film stock and back to digital to evaluate generative image stability and color fidelity. Final postproduction and sound mixing were completed at Sony Post Sound, bridging machine authorship with cinematic craftsmanship. The Bends ultimately stands as a case study in how generative tools can integrate with, rather than replace, traditional film departments—demonstrating a new standard of collaboration between AI systems and the artistry of production.

The Bends is an experimental AI film being produced by the Entertainment Technology Center (ETC).

Pathways is a hybrid AI film directed by Felipe Vargas that seamlessly merges live-action performance with AI-assisted cinematography and postproduction. Filmed primarily on iPhones using the Jetset app for real-time stabilization, metadata tagging, and on-set previs, the production achieved remarkable agility while preserving professional-grade image control. Acclaimed cinematographer Roberto Schaefer, ASC, worked with a small, mobile crew to design a visual language that could later be enhanced through AI-driven reconstruction. Using tools like ComfyUI, the team generated final-pixel backgrounds, simulated complex lensing effects, and rebuilt natural lighting conditions with precise continuity control—all while maintaining the emotional realism of practical performances.

A Virtual Art Department (VAD) was central to the production, generating temporary composited environments that guided both shot composition and director’s blocking. These AI-assisted previews allowed the creative team to visualize set extensions, refine camera placement, and test interactive lighting in near real time—bridging physical production with digital iteration. Once captured, footage was passed through a cloud-based workflow emphasizing security, creative intent mapping, and provenance tracking for IP protection. The result is a film that not only tells a moving story of two siblings reconnecting with their cultural roots but also functions as a proof-of-concept for responsible and artistically coherent AI-integrated filmmaking.

A scene from the ETC’s AI and live action hybrid film, Pathways.