Experimentation in Documentary Filmmaking

by Pablo Frasconi

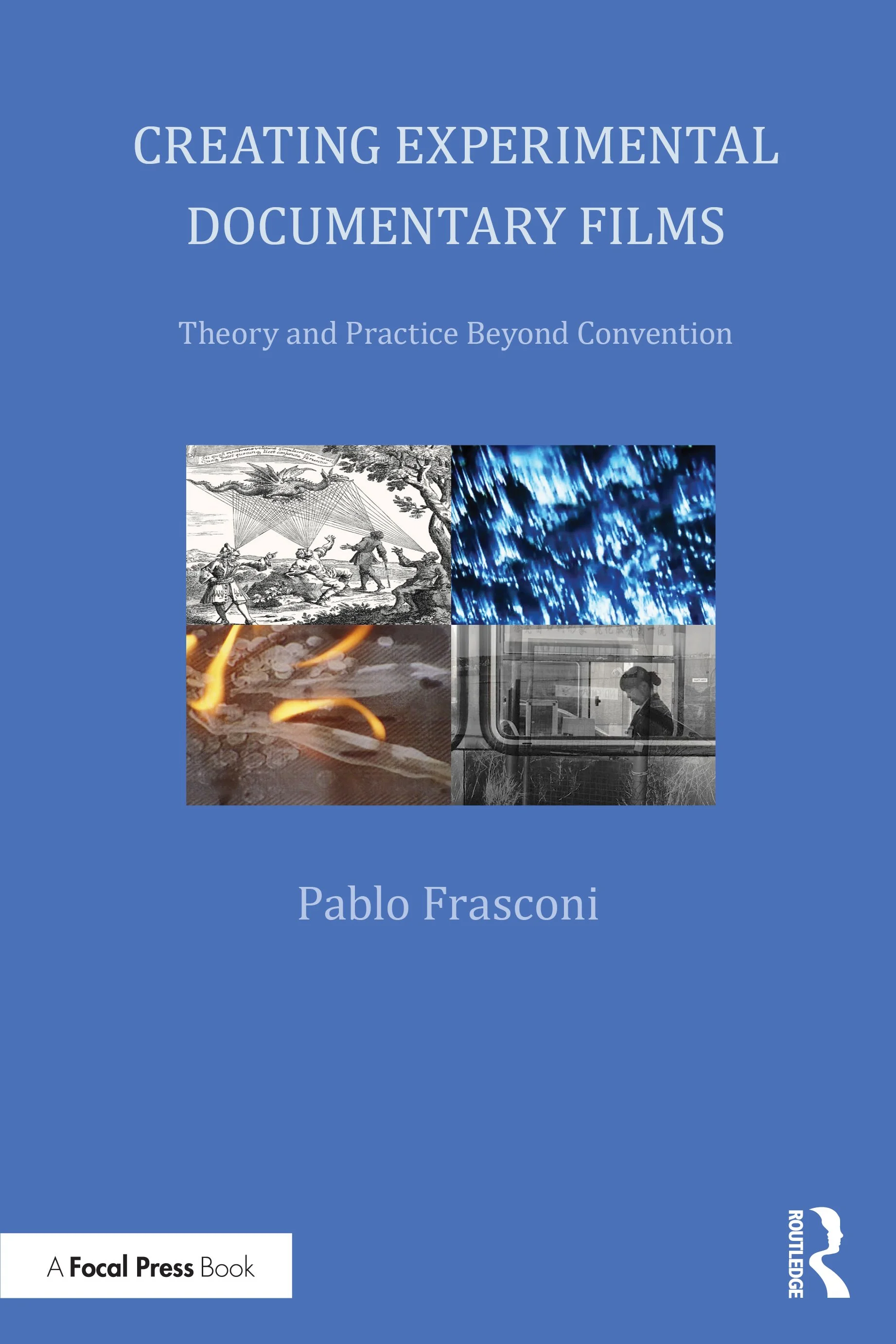

This article is adapted from Frasconi’s recent book Creating Experimental Documentary Films, a handbook for students who are approaching documentary for the first time as well as documentary filmmakers who are searching for new approaches, new subject matter, and languages of cinematic expression.

Experimental documentaries are undergoing unprecedented expansion. This is especially the case in social media like TikTok and Snapchat, streaming services sponsoring and purchasing new docuseries, theatrical distribution, immersive technologies which create or extend reality, and artificial intelligence creating documentary-like deepfakes. All of this inhabits a backdrop of a shrinking world in which interconnectedness, global travel, communication, and new creative collaborations and perspectives are developing, expanding, and thriving.

The term experimental documentary needs some fine-tuning. While “experimental” makes it sound like the creator might not have a clear goal in mind— that a film or digital experience is an experiment—that is usually far from the truth. An experimental documentary film might be unusual and hybrid and break with conventions, but it is a deliberate process involving, in my estimation, twelve attributes that include unique, exploratory ways of capturing space and light with a camera, especially exploring the relationship between representational and abstract images; expanded use of reification: translating abstract ideas into concrete images; exploration of previously unknown, mysterious, magical, or unexplainable subject matter, including underrepresented or taboo subject matter.

One example is the work of American experimental documentarian John Gianvito (USA, b. 1956), who captures traditional “B” roll as the spine of the film, which then becomes the film’s “A” roll, challenging conventional notions of documentary. His work, such as Profit Motive and the Whispering Wind (USA, 2007, 58 min), inspired by Howard Zinn’s book, A People’s History of the United States, is a visual meditation on the history of political activism in the US, consisting of shots of gravesites and monuments to those who fought for social justice interspersed with scenes of the natural landscape. The shot selection omits traditional forms of documentary that rely on interviews or voice-overs as the spine and “A” roll. Instead, it embeds the audience’s inquiry into place, tone, light, and texture.

Another unconventional use of the frame in a documentary is to capture the forbidden or taboo, such as the feature Hidden Letters (China, 2022) by Violet Du Feng and Qing Zhao. In this film, two people try to balance their lives as independent women in modern China while confronting the traditional identity that defines yet oppresses them. Du Feng wrote: “For centuries, women had their feet bound, and were confined to their chamber rooms. To give each other hope, they created a language that men did not understand. It was called Nüshu.” One subject in the film says: “The letters to our sisters were very private, to share our sufferings secretly.” When capturing private moments with fewer references to conventional compositions, documentarians are freer to experiment with visualization. As we might find in fiction filmmaking, this film uses carefully framed reflections, a selective color palette, and frames within frames as expressive tools.

CREATING EXPERIMENTAL DOCUMENTARY FILMS: Theory and Practice Beyond Convention by Pablo Frasconi book cover.

In Bill Viola’s (1951–2024) Hatsu-Yume (First Dream), 1981, we see a lifelong experimental documentarian who captured images of everyday life, mostly exteriors, re-interpreted by the frame, color, motion, texture, density, and rate of speed. Another unconventional method of exploring the frame is with an unmounted or removed lens on a camera. Pioneered by Stan Brakhage with analog cameras more than 25 years ago, it is known today as “lens whacking” or “free-lensing.” Brakhage sought to change what a camera captured by “wrecking its focal intention to achieve the early stages of impressionism.” In his film Commingled Containers (1997), he captured water splashing on the prism of his 16-mm camera, evaporating in the sun, reversed the sequence in editing, and, without a lens, captured stunning translucent 3D objects spinning, orbiting, and transforming, like microscopic entities moving into and out of darkness, emerging and disappearing in and out of infinite space.

Many of Brakhage’s films, once lost to decaying silver on acetate as well as chipping paint and scratches on the film itself, have been, since 2004, restored and screened at the Academy Film Archive in Los Angeles. Their inclusion in this collection is evidence of how experimental cinema—once considered marginal—continues to influence the mainstream.

Contemporary “lens whacking,” or removing the lens from its digital camera mount and holding it loosely in front of the camera’s film gate or sensor, creates an extremely narrow depth of field that distorts the image in unexpected ways. The result is the transformation of representational images into abstraction.

We can also take a step into sophisticated camera control with an inexpensive smartphone application, Filmic Pro, that transforms a smartphone into camera basics with its simple controls of intensity (f/stop), time (shutter), perspective (focal length), and monocular vision (aspect ratio). These features allow for much documentation beyond convention. It boasts “granular control of focus, exposure, frame rate, bitrate, audio, aspect ratios, gamma curves, and extensive film simulations.” This can allow for more expressive visual design and break away from the smartphone’s “point and shoot” default mode.

What Lies Beyond the Single Lens and Frame?

Multi-screen installations using documentary images are literally steps beyond the single frame. Agnes Varda (France, 1928–2019), whose work crossed genres and eras, said that three words were important in her work: “inspiration, creation, and sharing.” She invented multi-screen installations, trying “to bring together reality and its representation.” Bill Viola, who also worked in multi-screen installation, explored the connection and interplay between the outer world and the inner realm. He wrote: “I’m interested in how thought is a function of time. There is a moment when the act of perception becomes conception, and that is thought.”

Varda’s Patatutopia (2003) shows images of potatoes in various states of decay, a work inspired by her discovery of heart-shaped potatoes while making The Gleaners and I (France, 2000), a feature-length documentary about the gleaners who pick up food left in the field after harvest. In the center panel of Patatutopia, the heart comes to life as we hear respiration as 1,500 pounds of potatoes lie on the floor, and, at the exhibit’s opening, Varda wore a potato costume wired with speakers.

Today, new technologies are converging and re-integrating with an array of possibilities for the documentarian. Some blur the line between production and post-production, with new approaches to creating depth, merging realism with abstraction.

Ana Vaz (Brazil, b. 1986) creates film-poems which “travel through territories and events haunted by the consequences of internal and external forms of colonialism.” She adds visual layers to her images with digital tools, creating a hybrid aesthetic that captures the external disruptions of everyday traditions. In Apiyemiyekî? (2020), drawings made by native peoples in the Brazilian Amazon create a visual memory of the “violent attacks they were submitted to during Brazil’s military dictatorship.”

In Amérika: Bahía de las Flechas (Amérika: Bay of Arrows, 2016), Vaz takes “the camera itself as an arrow, a foreign body” and looks “for ways in which to animate, to awaken, to make vibrate again this gesture in the present—arrows against a perpetual ‘falling sky.’

In some cases, the images in a film may look like a documentary but may be created with artificial intelligence. Martin Luna (b. 1998) created Tomorrow Is (University of Southern California, 2023), entirely with artificial intelligence engines.

Some hybrid documentary paths abandon the single lens and frame as the foundational expressive tools. The line between “reality” and “representation” disappears. The work of Nonny de la Peña, a pioneer of documentary virtual reality places the viewer in actual events or reenactments. In We Who Remain (2017), the audience is placed in an active war zone, where civilians struggle to go on with their lives. In reenactments such as Use of Force (2010) and Hunger in Los Angeles (2012), the audience finds itself in other traumatic crises. De la Peña explains that these experiences create “a whole new full embodied experience that uniquely positions people to have a visceral experience and understanding of a news story.”

Reenactments have been a common hybrid form of documentary for generations, and the value of provoking trauma in the viewer/participant can have psychological, cultural, and/or artistic value. At best, Dr. Brene Brown tells us that feeling others’ trauma fuels empathy and connection. She writes that there are four qualities of empathy: “1) the ability to take the perspective of another person, or recognize their perspective as their truth, 2) staying out of judgment, 3) recognizing emotion in other people, and communicating that, and 4) feeling with people.”

Critic Roger Ebert famously said “movies are like a machine that generates empathy.” It is a medium which allows us to step into someone else’s shoes and experience in a way that the real world does not allow. Expanding the possibilities and approaches available to documentarians, both within and beyond the frame, can only enrich this magical empathy machine and just might be a significant force for change in the world.

Pablo Frasconi studied with experimental filmmaker Stan Brakhage, filmmaker & historian Jay Leyda, and the father of Canadian film studies, Peter Harcourt. He teaches film production, mentors MFA thesis films, and coordinates the first year of the MFA Production Division at the School of Cinematic Arts. He also leads the Global Exchange Workshop, a program in which students travel between Beijing and Los Angeles to collaborate on documentaries.