Guardians of Hollywood’s Memory: The Warner Bros. Archives and the Iron Mountain Partnership

by Lorena Sanchez

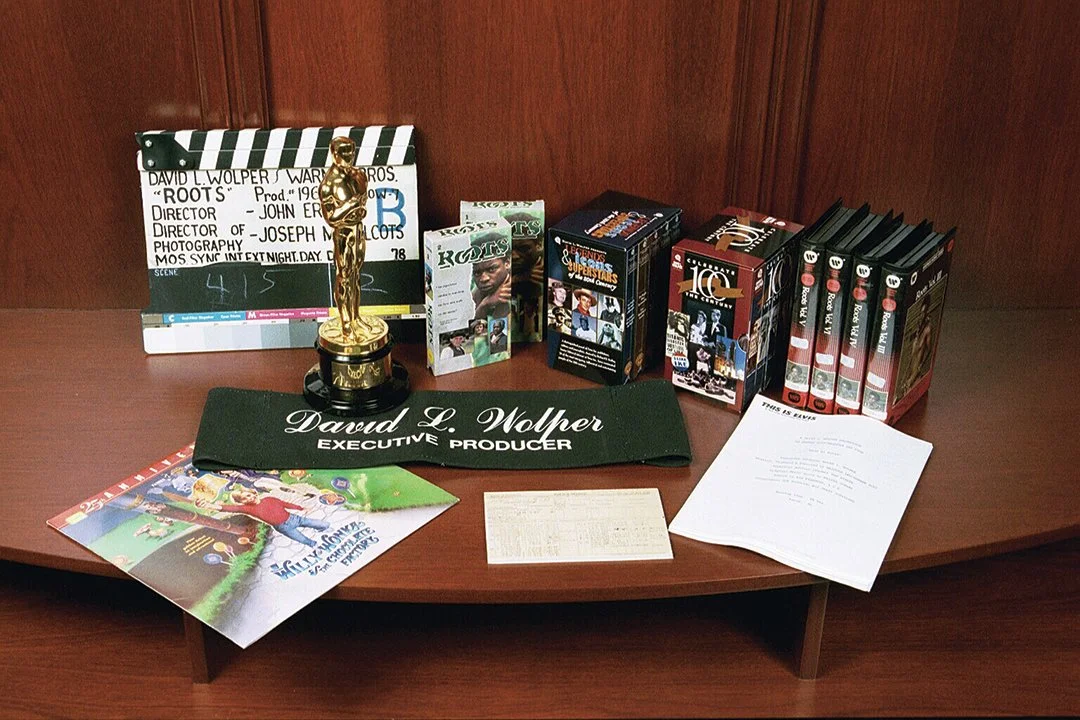

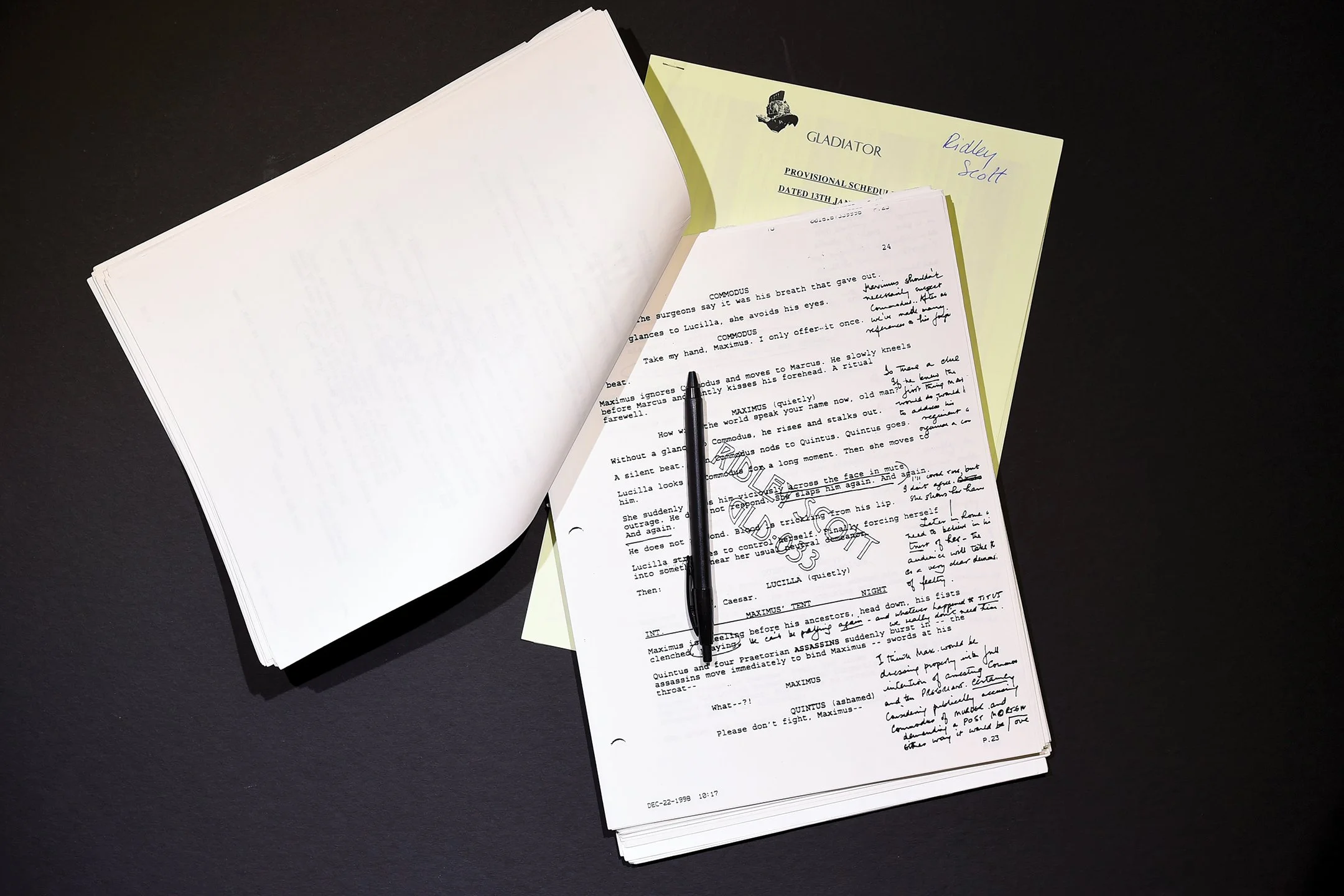

When you open a box in the Warner Bros. Archives—now preserved in partnership with Iron Mountain—you never know what you’ll find: a letter from Bette Davis scolding Jack Warner, a memo from the Breen Office objecting to a scene, or a hand-annotated script from a film that helped define American cinema.

“It’s unbelievably unique,” says Bree Russell, archivist and alumna of USC’s School of Cinematic Arts. “It’s a studio archive that covers the years from 1923 to 1968, when Jack Warner sold the studio to Seven Arts.”

The Warner Bros. Archives, or WBA, is one of the largest and most comprehensive single-studio archival collections in the world, documenting the inner workings of a Hollywood powerhouse through memos, contracts, publicity stills, scripts, production notes, and even music scores.

The collection arrived at USC in 1977, when Warner Bros., seeking long‑term preservation and scholarly access, donated thousands of boxes to the university. Today, those materials—about 20,000 boxes—are preserved with Iron Mountain, the global leader in secure preservation, whose climate‑controlled Englewood, CO facility maintains the collection with the same precision it uses across its information‑security operations.

Safeguarding the WBA is not merely storage for Iron Mountain—it is core to the company's mission to protect the world's most valuable and vulnerable information. Andrea Kalas, vice president of Media and Archival Services at Iron Mountain, sees the work as both an operational responsibility and a moral one.

“Archivists are charged with a duty of care to materials,” Kalas explains. “Our number one job? Don’t lose stuff! You’ve been given the responsibility to make sure that when somebody needs something you’re holding, it will be there and remain available.”

That philosophy underpins Iron Mountain’s partnership with USC: precise environmental controls, rigorous preservation workflows, a dedicated media‑trained staff, and a shared commitment to maintaining stable, secure, long-term access for scholars around the world.

Iron Mountain’s role extends far beyond vaults. The company provides environmental monitoring, logistics, redundancy systems, and digital infrastructure—ensuring the archive remains resilient and accessible for decades. “Iron Mountain is essential to this archive’s continuity,” Russell says. “None of this work would be possible without their consistent stewardship.”

Iron Mountain executives joined USC School of Cinematic Arts at Sundance 2024 to explore the future of cinema through archival preservation.

For Russell, who earned her master’s degree in Cinema & Media Studies at USC, the archive is not a static repository but an active teaching tool. “I work with an undergraduate class where they use the archives,” she says. “I pull folders—everything from legal debates around Meet John Doe to production files. It makes the studio’s history tangible.”

Faculty and students from across the country regularly visit the WBA. Over the years, USC has mounted numerous exhibits drawn from the collection. “The biggest was on Warner Bros. films during World War II,” says Sandra Garcia-Myers, head of the Cinematic Arts Library. “The relationship between the studio and USC has evolved in a reciprocal way.”

For Russell and Garcia‑Myers, Iron Mountain’s preservation work ensures the archive remains usable for what makes it invaluable: revealing the dynamics of the Hollywood studio system. “Film history is cultural history,” Russell says. “For one of the original big studios, having documents directly from the source is extraordinary.”

Annotated scripts, memos written in moments of conflict, and correspondence shaped by censorship boards illuminate the negotiations that still echo through modern filmmaking. “You see the conversations—when a filmmaker wants something and the studio pushes back, or the Breen Office intervenes,” Russell explains. Garcia‑Myers adds, “We think films will last forever, but sometimes they don’t. The paper footprint—the memos, scripts, production notes—helps scholars understand how films were made, even if the film itself disappears.”

The WBA attracts researchers from around the world. “Graduate students from Europe come here just to see it,” Garcia‑Myers says. As research expands into sociology, business, and cultural studies, the archive’s relevance grows. “It’s not just about stars and films,” she says. “People want to know why audiences went to movies, what they saw, and what it meant.”

Kalas sees emerging technologies expanding that reach even further. “AI opens up entirely new avenues for discovery,” she says. “You can run visual searches—‘Show me a car crash at sunset’—and instantly surface relevant materials.” These tools, built atop Iron Mountain’s cataloging and metadata systems, help connect scholars around the world to items they might never otherwise encounter. But Kalas is clear that innovation only works when the physical foundation is secure. “Digital tools don’t matter if the originals vanish,” she says. “Iron Mountain helps ensure they don’t.”

Russell lights up when she talks about her favorite discoveries. “There’s the fan in me—looking at Bette Davis’s file, her stationery, her handwriting. Holding something she wrote is incredible.” She’s equally drawn to the everyday labor behind the system. “I want to know more about the secretaries tracking all this material. They exist in the archive, but they’re harder to find—it takes digging.”

That detective work is part of the joy. “It’s like being a forensic accountant,” Russell says. Hidden in the paperwork are stories of budgets, casting decisions, shooting locations, and the countless practical choices that shaped the final films.

Kalas emphasizes the need for continued collaboration to ensure public access. “Advocate, advocate, advocate,” she says. “Give institutions the information they need to free up resources so you can care for your archive.” She notes that public–private partnerships—like USC and Iron Mountain—are essential to keeping these materials open, studied, and culturally meaningful.

For both archivists, the Warner Bros. Archives are far more than a cache of studio documents. They are a living record of Hollywood’s imagination—a mirror of American culture across decades—preserved through the ongoing work of USC archivists and Iron Mountain specialists. “Archives don’t generate money; they’re costly,” Russell says. “But they preserve who we are—our conversations, conflicts, and creativity. They protect our collective imagination.”

Ridley Scott’s original Gladiator script is among the many treasures preserved in the Warner Bros. Archives, housed at the USC School of Cinematic Arts.